Uncovering How Exercise Impacts Blood Vessel Health in Diabetes

The relationship between exercise and vascular function has always been full of tricky parts and hidden complexities, especially when it comes to adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Recent research has shed light on how different bouts of aerobic exercise affect the health of blood vessels in people with T2DM versus their healthy peers. In this editorial, we take a closer look at the study’s findings with an eye for the fine points and subtle details that define the exercise response in this population.

Delving into the Blood Vessel Response Post-Exercise

One of the central observations in recent investigations centers on the way blood vessels adjust immediately after exercise. To simplify, the study examined two key indicators of vascular health: flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and flow-mediated slowing (FMS). Both measures reveal how well the blood vessels relax and contract in reaction to increased blood flow, but each offers a slightly different glimpse into the nitty-gritty of vascular function.

The results indicated that a high-intensity interval exercise (HIIE) session led to an immediate reduction in FMD and a concurrent increase in FMS in older adults with T2DM. These changes, however, were only temporary, returning to normal values after about an hour. Conversely, moderate-intensity continuous exercise (MICE) tended to boost FMD without altering FMS much, suggesting that the intensity of aerobic activity may play a key role in how blood vessels respond acutely in diabetic individuals.

Examining the Effect of High-Intensity Interval Exercise on Vascular Function in Diabetes

Acute bouts of high-intensity interval exercise are often seen as both challenging and, at times, a bit intimidating for many individuals, especially those with health complications like T2DM. The study’s findings revealed that HIIE can trigger a temporary reduction in FMD, which is a marker for the blood vessels’ ability to dilate following increased blood flow. Simultaneously, there was an increase in FMS, a newer indicator reflecting a decrease in arterial stiffness following reactive hyperemia. These swift changes underscore the delicate balance within our vascular system and the complicated pieces involved in interpreting exercise-induced responses in diabetes.

For many, the immediate post-exercise state can feel overwhelming—imagine a sudden drop in a physiological parameter that’s usually considered a sign of good health. However, the short-lived nature of these changes suggests that while HIIE might temporarily challenge the blood vessel’s reactivity, it doesn’t necessarily realign the overall vessel health. Instead, it could be part of a process where the body orchestrates adjustments to strengthen vascular function over time.

To summarize, the following points capture the key effects of HIIE in older adults with T2DM:

- Immediate decrease in FMD (indicating a transient reduction in endothelial function).

- Concurrent increase in FMS (reflecting a temporary lessening of arterial stiffness).

- Normalization of these vascular responses within 60 minutes post-exercise.

How Moderate-Intensity Continuous Exercise Boosts Endothelial Health in Diabetic Conditions

Unlike HIIE, moderate-intensity continuous exercise tends to be less nerve-racking and carries a different set of vascular responses. For older adults with T2DM, MICE not only avoids the short-term drop in FMD but in fact, results in an increase. This suggests that the lighter, sustained effort may be more comfortable on the body’s blood vessels, thereby offering a pathway to improved endothelial function over time.

Several factors might contribute to this effect. Moderate exercise produces less oxidative stress—a major culprit in diluting nitric oxide (NO), a key molecule that enables blood vessel relaxation. In contrast, the high-intensity bursts in HIIE can spike the production of superoxides, which may transiently counteract the benefits of NO, leading to temporary stiffening. This phenomenon highlights the small distinctions between types of exercise in how they affect the body’s blood flow dynamics.

For those considering exercise routines in the context of T2DM, MICE might represent a safer and more predictable way to upregulate vascular function. The increased FMD post-MICE can be seen as a positive, reinforcing sign that moderate exercise may foster healthier blood vessels without the drawback of immediate adverse reactions.

Understanding Flow-Mediated Dilation and Flow-Mediated Slowing: The Fine Points

Flow-mediated dilation and flow-mediated slowing are tools used to poke around the subtle parts of vascular health. FMD assesses the ability of arteries to widen in response to increased blood flow, a process that largely depends on NO. A higher FMD is generally taken as a sign of better endothelial performance. FMS, on the other hand, measures the rate at which pulse wave velocity decreases after blood flow is stimulated. While these measurements originate from the same vascular process, they capture different twists and turns of the body’s response mechanisms.

It is interesting to note that the study found an inverse relationship between FMD and FMS in older adults—when FMD went down, FMS went up. This suggests that FMS can act as a complementary measure, offering another layer of insight into how exercise impacts the body’s blood vessel flexibility.

This dual approach is especially beneficial when dealing with the tricky parts of managing a condition like T2DM, where the blood vessels can be loaded with problems due to both age and metabolic challenges. Understanding both FMD and FMS can equip clinicians and exercise professionals with a better picture of vascular health and guide them in figuring a path forward for personalized exercise prescriptions.

The Role of Cardiovascular Fitness in Managing Vascular Reactions

Another critical piece in the puzzle is the influence of overall cardiovascular fitness. It turns out that higher cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) may help smooth over the temporary reductions in FMD following high-intensity exercise. In simpler terms, individuals with better fitness levels tend to bounce back faster from the temporary vascular perturbations induced by challenging activities. This factor is especially important for older adults with T2DM, who often have lower CRF compared to their healthy peers.

The study noted that lower CRF in T2DM was linked with more pronounced early vascular changes. This creates a situation where the benefits of exercise must be balanced against the inherent lower capacity of the cardiovascular system to manage sudden changes. In practical terms, those who engage in regular exercise stand a better chance of maintaining or even enhancing their vascular health over time, thanks largely to improved cellular responses and the upregulation of protective enzymes.

For those planning exercise programs for T2DM patients, these findings underline the importance of building up fitness gradually. Starting with moderate-intensity sessions and progressively adding in higher-intensity elements can help steer through the initial nerve-wracking adjustments, ultimately leading to more sustainable improvements in vascular function.

Practical Considerations for Exercise in Type 2 Diabetes

As we consider the nitty-gritty of implementing exercise strategies for people with T2DM, a few practical points emerge that can be organized into clear steps:

| Step | Recommendation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Start with Moderate-Intensity Exercise | Begin with MICE to promote endothelial function without overwhelming the system. |

| 2 | Assess Fitness Levels | Perform baseline tests—such as cardiopulmonary exercise testing—to tailor exercise prescriptions. |

| 3 | Monitor Vascular Responses | Use measurements like FMD and FMS to track how blood vessels respond immediately after exercise. |

| 4 | Gradually Introduce Higher Intensities | If appropriate, incorporate HIIE carefully while monitoring short-term vascular adjustments. |

| 5 | Regular Reassessment | Periodic testing of vascular function to adjust the exercise program as needed. |

This stepwise plan can help both patients and clinicians get around the confusing bits of exercise prescription in T2DM and reduce the risk of potential short-term vascular disturbances while maximizing long-term benefits.

Digging Into the Role of Oxidative Stress and Nitric Oxide

One of the complicated pieces in the vascular response puzzle is the role of oxidative stress. During high-intensity exercise, there is a marked increase in free radicals like superoxides. These molecules can react with nitric oxide—an essential vasodilator—to form peroxynitrite. This reaction, in turn, diminishes the availability of nitric oxide, leading to a temporary reduction in FMD. For those curious about the scientific details, this is one of the hidden complexities that can make high-intensity exercise feel somewhat off-putting for older diabetic patients.

Moderate exercise, by contrast, tends to produce less oxidative stress. With fewer free radicals popping up during the workout, there is a better chance that nitric oxide will retain its vital role in encouraging blood vessel dilation. This difference in oxidative load between HIIE and MICE forms a key distinction between these exercise modalities and suggests why MICE might be more attractive for vascular health in populations where endothelial function is already compromised.

Here is a simplified overview of the process:

- High-Intensity Exercise: Increased free radical production → More reaction with nitric oxide → Temporary decrease in blood vessel relaxation.

- Moderate-Intensity Exercise: Lower free radical surge → Better nitric oxide retention → Enhanced blood vessel relaxation.

Using Blood Pressure and Heart Rate as Markers of Vascular Change

Another important area to consider is the role of blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) in monitoring vascular responses. The study observed that while the HR remained elevated in the early minutes after high-intensity exercise, BP did not show significant post-exercise changes. For many, this might be a relieving detail as it suggests that, despite some initial unstable twists and turns, the overall blood pressure regulation remains intact post-exercise.

It is worth noting that the phenomenon known as post-exercise hypotension (a temporary lowering of BP after exercise) has been inconsistently reported in clinical populations. In this study, the absence of significant BP fluctuations might partly be explained by the participants’ normal baseline BP values. This information can be useful to clinicians who are weighing the risks and benefits of exercise prescriptions in people with raised cardiovascular risk.

When evaluating these markers, the following observations become noteworthy:

- Elevated HR post-HIIE suggests the body’s immediate need to stabilize after intense bursts of activity.

- Stable BP post-exercise indicates that the short-term adverse effects on endothelial function (as seen in FMD and FMS changes) may not extend to major cardiovascular parameters.

- The differences in heart rate responses between young, older, and diabetic populations underscore the importance of individualized exercise programs.

Balancing Exercise Intensity: Safety Versus Benefits

One of the nerve-racking decisions faced by exercise professionals and individuals with T2DM is choosing the right intensity level to get the most benefit without too many risky side effects. On one end of the spectrum, high-intensity interval exercise can be a powerful trigger for cardiovascular adaptations yet may temporarily impose a burden on an already stressed vascular system. On the other, moderate-intensity exercise appears to be safer, offering a more consistent increase in beneficial outcomes such as FMD without the transient negative effects on FMS.

This balancing act calls for a personalized approach. The following table provides a snapshot comparison of HIIE and MICE in the context of vascular responses:

| Aspect | High-Intensity Interval Exercise (HIIE) | Moderate-Intensity Continuous Exercise (MICE) |

|---|---|---|

| FMD Response | Temporary reduction immediately post-exercise | Increase in FMD showing improved endothelial function |

| FMS Response | Increase, reflecting short-term arterial stiffness changes | No significant change |

| Oxidative Stress | Higher; more free radicals produced | Lower; more tolerable for endothelial cells |

| Heart Rate | Elevated post-exercise with prolonged recovery | Moderate elevation with quick stabilization |

| Suitability for T2DM | May be too challenging for some due to transient vessel alterations | Better tolerated with positive enhancements in blood vessel function |

This overview reinforces the idea that while both exercise types have their roles, the moderate, consistent approach may be best suited for those who need a gentler stimulus for improving vascular health without overloading the system.

Bringing It All Together: Clinical Implications and Future Directions

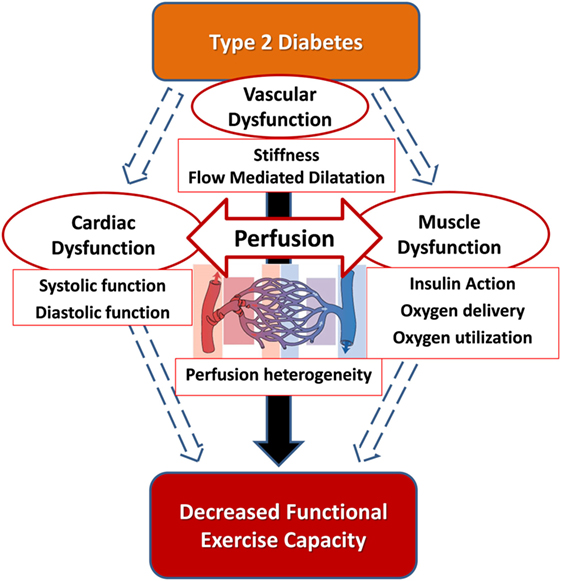

When dealing with type 2 diabetes, the vascular system is already fighting against tangled issues like reduced nitric oxide bioavailability, oxidative stress, and low-grade inflammation. The challenge lies in choosing exercise types that not only improve overall health but also work in sync with the body’s nuanced response mechanisms. The study’s findings offer promising insights by demonstrating that while both high-intensity and moderate-intensity exercise can elicit changes in blood vessel function, the mode and timing of these changes differ significantly.

Clinically, such observations are super important. A transient decline of 6% in FMD might seem troubling at first glance, given that even a 1% drop is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. However, this brief dip following high-intensity exercise might also act as a trigger for adaptive improvements over the long haul. In other words, the temporary stress is a necessary evil—a sort of controlled challenge that encourages the body to strengthen its vascular responses over time. Conversely, an immediate upturn in FMD following moderate exercise is reassuring and might suggest a safer approach, at least in the short term.

Future research is needed to clarify several open questions. For instance, how do repeated sessions of either HIIE or MICE affect vascular health over months or even years in those with T2DM? What is the precise role of insulin therapy and other medications in modulating these immediate exercise-induced changes? And finally, can personalized exercise prescriptions based on real-time vascular monitoring lead to better cardiovascular outcomes for patients? These are just a few of the areas that require further exploration as we work through the puzzling and sometimes intimidating details of exercise science in clinical populations.

Exploring the Practical Implications for Exercise Prescription

Given the evidence presented, it is clear that exercise prescriptions for people with T2DM need to be highly individualized. Here are some key takeaways for clinicians and fitness experts when designing exercise programs for this population:

- Assessment First: Before prescribing any exercise regimen, conduct comprehensive assessments of both cardiovascular fitness and vascular function using FMD and FMS measurements.

- Start Slowly: For those with lower CRF or advanced T2DM, begin with moderate-intensity sessions to avoid overwhelming the blood vessels.

- Monitor Responses: Continuous monitoring post-exercise can help identify transient changes and guide adjustments in exercise intensity or duration.

- Progress Cautiously: Gradually introduce higher-intensity elements as fitness improves and as the body demonstrates an ability to recover efficiently from initial vascular perturbations.

- Consider Medication Effects: Be aware of potential interactions between insulin therapy, oral glycemic agents, and exercise-induced vascular responses.

This blend of careful assessment along with gradual progression empowers both the patient and the clinician to find a path that maximizes benefits while minimizing any off-putting side effects. Such an approach not only builds cardiovascular strength but also reinforces a patient’s confidence in managing their condition through physical activity.

Personalizing Exercise Programs: A Tailored Approach for Diabetic Patients

One of the key messages emerging from the study and our discussion is that one size does not fit all. Given the considerable individual variability in vascular function responses—especially in a group as diverse as older adults with T2DM—exercise programs must be highly personalized. Working through the small distinctions in the way each person’s blood vessels respond to exercise is critical for long-term success.

Personalization can include:

- Tailoring the number of exercise bouts and duration to match energy expenditure goals.

- Adjusting intensity based on cardiorespiratory fitness levels.

- Monitoring recovery times to determine how soon and how intensely subsequent sessions can be performed safely.

- Incorporating both high-intensity and moderate-intensity training at different phases, thereby balancing the temporary vascular irritations with long-term benefits.

This tailored approach takes into account the fact that multiple factors—including age, fitness level, medication use, and overall vascular health—play a role in how exercise impacts each individual. By staying attuned to these fine shades of difference, healthcare providers can help patients “take the wheel” in managing their own health more effectively.

Addressing the Confusing Bits: Future Research and Considerations

Despite these encouraging findings on the effects of acute exercise on vascular function in T2DM, several confusing bits remain unresolved. For instance, the precise long-term implications of repeated high-intensity versus moderate-intensity bouts are still on edge and call for further study. Additional research is needed to:

- Chart the timeline of vascular adaptations after repeated exercise sessions over weeks and months.

- Examine whether acute reductions in FMD post-HIIE eventually translate into sustainable improvements or represent a temporary challenge that might increase short-term risk.

- Determine how variations in insulin therapy and the use of other medications affect the immediate and long-term vascular responses to different exercise intensities.

- Assess the role of other promising markers of vascular health, such as circulating endothelial progenitor cells or inflammatory mediators, in conjunction with FMD and FMS.

By tackling these questions, future studies will help steer through the tangled issues in exercise physiology as it relates to diabetes management. They will also provide much-needed guidance to clinicians and patients alike, ensuring that exercise prescriptions are based not only on current evidence but also on robust long-term outcomes.

Making Your Way Through the Twists and Turns of Vascular Health

Managing a condition like type 2 diabetes is loaded with challenges that extend to every corner of one’s health—including the fine points of vascular function. The study we reviewed today illustrates that the body’s reaction to exercise includes both beneficial and temporary disruptive changes. Even though the immediate effects of HIIE might seem intimidating due to their transient negative impact on FMD, these responses should be understood as part of a broader adaptive process. Conversely, the positive shifts seen with MICE underscore the potential of more moderate activities to safely enhance blood vessel function over time.

For patients and clinicians alike, it’s crucial to recognize that both high-intensity and moderate-intensity exercises can have a place in a comprehensive health plan. By combining careful assessments, personalized exercise programs, and an understanding of each modality’s benefits and limitations, it’s possible to navigate the complicated pieces of T2DM management successfully.

Key Takeaways for Clinicians and Patients

Let’s summarize the key points to remember as you figure a path through the exercise recommendations for T2DM:

- Acute Exercise Effects: High-intensity exercise can lead to temporary reductions in FMD and increases in FMS, which normalize within an hour. Moderate exercise, on the other hand, boosts FMD without causing adverse shifts in FMS.

- Role of Oxidative Stress: High-intensity workouts may generate more free radicals, temporarily reducing nitric oxide availability, whereas moderate exercise exerts a milder oxidative load.

- Personalized Programs: Exercise prescriptions should be tailored to individual fitness levels, with gradual progression from moderate to higher intensity, depending on the patient’s response.

- Monitoring Vital Signs: Regular monitoring of heart rate, blood pressure, and vascular function markers is super important for adjusting exercise intensity safely.

- Future Research: More studies are needed to fully understand the long-term benefits versus risks of the differing exercise modalities, especially concerning repeated sessions and medication interactions.

Wrapping Up: Striking a Balance in Exercise for Diabetes

In conclusion, the balancing act between high-intensity and moderate-intensity exercise in type 2 diabetes is a fine one. While HIIE can temporarily challenge the blood vessel’s flexibility, it might also serve as a powerful trigger for long-term adaptations. MICE, with its more stable and positive short-term outcomes, provides an essential, less intimidating entry point for individuals who may feel overwhelmed by the demands of a high-intensity workout routine.

This editorial is not meant to single out one approach over the other but to emphasize that a well-rounded and personalized exercise program is key. As research continues to dig into these subtle details, both clinicians and patients are encouraged to work together, carefully adjusting exercise regimens to ensure that the twists and turns of vascular health are managed effectively.

Future Perspectives: Personalized Exercise as a Must-Have in Managing T2DM

Looking ahead, the concept of precision exercise medicine is rapidly gaining ground. With advancements in wearable technology and continuous monitoring, we are on the verge of a new era where exercise prescriptions can be dynamically adjusted based on real-time vascular responses. Such an approach would allow patients with T2DM to tailor their workout intensity and duration, ensuring that their blood vessels are rewarded with the most effective stimulus without being overloaded by temporary stress factors.

This emerging field is all about finding the right balance between challenging the body and providing a safe, manageable avenue for improvement. In this context, both HIIE and MICE have their roles, but their optimal integration will likely differ from person to person. By taking the wheel and making informed choices, patients can proactively address the hidden complexities of diabetes management and potentially reduce the long-term risks of cardiovascular events.

Final Thoughts: Empowering a Healthier Future Through Smart Exercise Choices

For individuals living with type 2 diabetes, the message is clear: exercise remains a cornerstone of health, but the path forward is loaded with twists and turns that require careful consideration. Whether you’re just starting out with moderate-intensity activities or gradually incorporating high-intensity intervals as your fitness improves, the aim is to foster an environment where your blood vessels can work efficiently without being overwhelmed by sudden changes.

As we continue to dig into the subtle details and fine shades of difference in exercise responses, remember that consistency and personalization are your best allies. The journey is as much about discovering what works best for your body as it is about benefiting from the long-term adaptations that exercise can promote. The insights from the latest study open up new avenues for optimizing exercise prescriptions, ensuring that the choices you make today build a healthier tomorrow.

Conclusion

In wrapping up, it is clear that the relationships among exercise intensity, vascular function, and type 2 diabetes are full of tangled issues and small distinctions that can have significant clinical implications. By understanding these acute responses—whether it’s the temporary reduction in flow-mediated dilation after high-intensity exercise or the encouraging boost observed with moderate exercise—healthcare providers can better support patients in managing their condition.

Although there remain several nerve-racking uncertainties and questions that future research needs to answer, the current evidence underscores the importance of personalizing exercise programs. In doing so, both the immediate and long-term vascular health of people with type 2 diabetes can be optimized, paving the way for enhanced quality of life and reduced cardiovascular risk.

Ultimately, an informed, balanced approach to exercise in T2DM is not only a smart strategy—it is essential. With continual advancements and a commitment to working through the overwhelming bits and fine points, the future of diabetes care may well be revolutionized by how we take control of our aerobic activity and harness its many benefits.

Originally Post From https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-10865-7

Read more about this topic at

Vascular Adaptation to Exercise in Humans

Advances in exercise-induced vascular adaptation